Post by SCHS Intern: Aaron Sather

The First World War, also often called the Great War or the War to End All Wars, was a massive conflict that has shaped the world in numerous ways. It marked the end of many Empires such as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, German Empire, Russian Empire, and Ottoman Empire. It was also a beginning for many new Nation-States that were formed out of remains of these Empires. While some Empires and Nations were involved in the conflict directly for all four years, the involvement of the United States is radically different than those on the continent of Europe. Many isolationists were antagonistic towards going to war, but eventually war was declared and the United States directly involved. Everyone in the United States, the State of Minnesota, as well as Scott County was involved in the conflict to a varying degree.

The first and most obvious avenue of involvement for American men in the war was direct military service. When the United States declared war in the Spring of 1917 the US Navy, though expanded due to the relationship between naval power and empire building, had limited utility due to the prevalence of U-Boat tactics. Dreadnoughts could blockade ports but engagements between naval squadrons remained limited. Meanwhile the US Army was grossly undermanned and ill equipped to fight the war expected of them on the Western Front, and later in the east against the rising Bolshevik threat in Russia. The United States needed to recruit, train, equip, and feed its Army before deploying the American Expeditionary Force to Europe. This process took months, and it was not until the summer of 1918 that the AEF began arriving in France en masse, often still lacking adequate arms and training. Many would receive weapons and training from the French. All states and counties in the United States were expected to provide men for the war effort. Scott County has changed drastically since the First World War as it was much more agricultural then. Being a food resource rather than a military manpower resource less enlistment was expected of Scott County to preserve its workforce and keep food flowing out of its fields. Even so 453 people were enlisted for military service from the county, 14 of whom would perish in service to their country. While enlistment rates for the county were at half the national average, the casualty rates remained the same as the rest of the nation. The brutality of the Great War is what drove these casualty statistics.

The type of combat varied incredibly across all fronts. From the brutal maneuver warfare of the massive Eastern front, to the chaotic asymmetrical warfare of the Middle East and Africa fighting was brutal. The Great War often remembered through the lens of the Western Front. Static lines were literally dug in the ground and the fighting descended into trench based warfare. Machines were developed to gain an advantage over the enemy, often with an incredible capacity to end human life. Tanks were developed to smash through heavily fortified lines, airplanes were used to reconnoiter and harass enemy positions (including civilians) and chemical weapons were developed to spread terror and death across vast swaths of territory. All off this technological development came due to the need of ascendancy on the battlefield and contributed to the wars brutality.

The American Expeditionary Force, under General John “Black Jack” Pershing, arrived in France and was engaged in horrendous trench warfare. There are many battles that display the severity and danger of the war, but the Battle at Verdun shows the horror that was the Great War the men from Scott county would find themselves in. General Falkenhayn, the German mastermind behind the battle, planned to “bleed France white” by taking the French village of Verdun and the surrounding forts. This plan was not to gain Verdun for any strategic importance but rather than to kill as many French soldiers as possible. Verdun was a place of great importance to French pride and so they defended it with vigor. The French motto “Ies ne passeront pas” or “They shall not pass” appeared in French propaganda. Thousands of French soldiers came to the defense of Verdun, some claim around 60% of the entire French army was rotated through the Verdun lines over the course of the 9 month 3 week and 6 day battle, and thousands died in the brutal battle of attrition. Artillery was used so extensively during the battle that trees still struggle to grow in some places around the site of the battle. In the end the French held, but their victory was a pyrrhic one. This was the type of war the American men were entering.

American involvement would allow French and British Units to finally receive much needed support, stepping in to bolster the Anglo-French lines after nearly three years of attrition and loses. American units were not broken up and assigned to allied units as Pershing wanted the AEF to stay American, though African American Units (the military was still segregated) were loaned to the French who had no issue using colored troops. A notable example of African American men in the war are the Harlem Hellfighters or the 369th Infantry Regiment, getting their nickname from the enemy and not themselves. After helping their allies hold the line the allies went on the offensive. Once enough Americans had arrived in France for the AEF to mount their own massive Meuse-Argonne Offensive, part of the greater 100 Days Offensive that finally pushed German forces back beyond the Hindenburg Line. Their lines shattered and now facing a combined Anglo-French-American Offensive free to maneuver unrestricted by prepared defenses and their people starving the German Empire signed the Armistice on November 11th, 1918. Though men were the ones who fought the war they were not the only ones involved in the it.

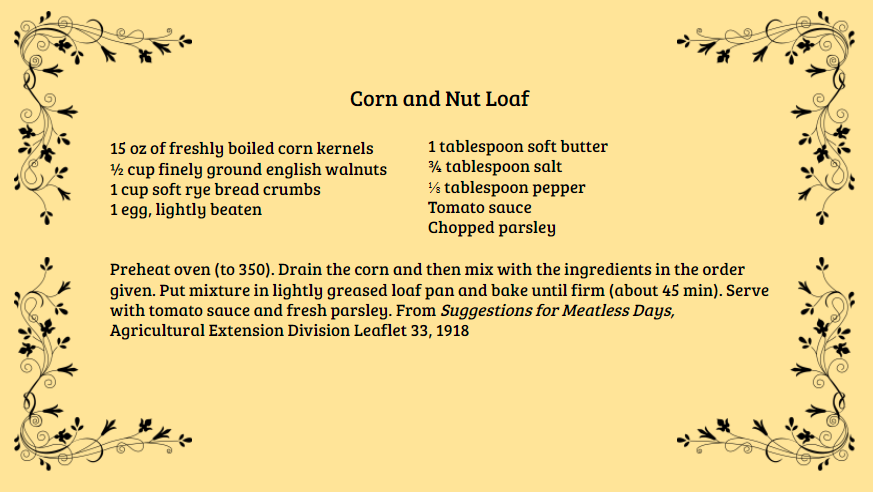

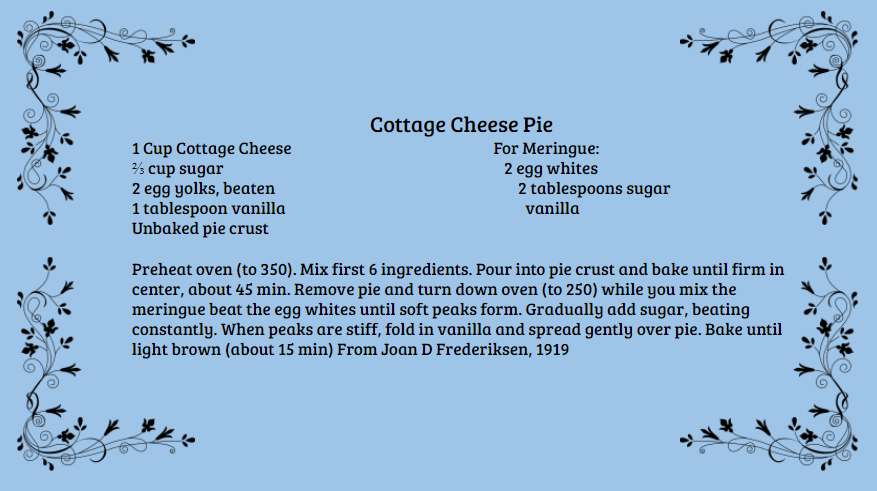

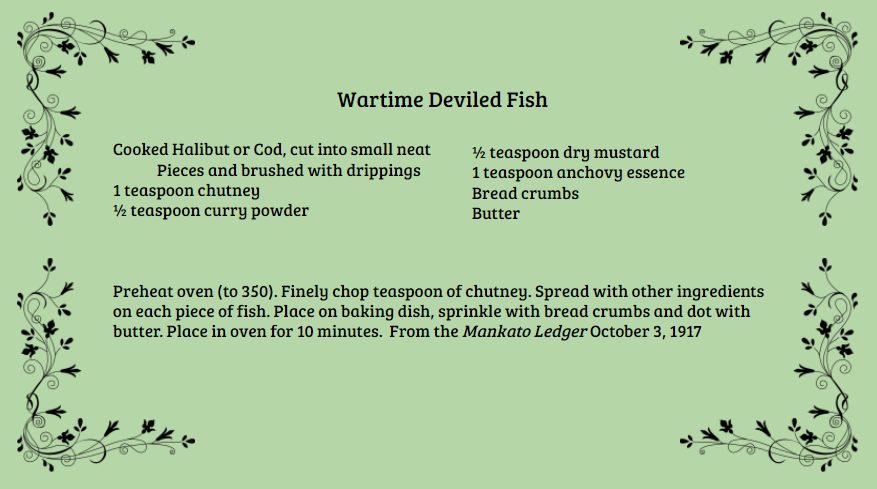

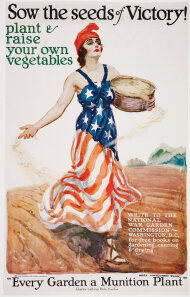

Men were the ones who were almost always on the frontlines of the war doing the fighting, asides from Women’s Battalions of Provincial Russian Government, but women also contributed greatly to the war effort. Women contributed to the war effort in whatever ways that they could. Some would become nurses and actually join the military such as the US Navy, caring for the sick and the wounded and being with the dying. Others would join the Red Cross, working to collect supplies to support the war effort and helping in any ways that they could. Even by writing simple letters to their husbands, sons, or brothers ensuring that all was fine on the homefront was crucial to the war effort. Commanders needed their soldier’s minds focused on what they needed to do, not the what-ifs of home. These women were not only writing letters saying things were OK with the family, they were the ones who actually mad things OK. As the heads of the household women took on a new double burden if a male left their household. Not only would they have to still cook meals for their families to eat, no easy feat due to rationing, but in some cases, they needed to step into the male’s place in the economy by also working. Some British Women would work night shifts at a munitions plant, leave work early in the morning to get in line at the grocer, get home and take care of the house and family, and then go back to work in the late evening, somehow trying, or not, to fit in sleep. Though Scott County women did not experience the direct danger of being near a warzone they still made great sacrifices and contributed to the war effort.

Americans contributed to the war effort in any way that they possibly could. Men, many in Scott County, would stay at home and continue farming to provide food for the war effort. Others would go off to fight and die thousands of miles away from all that they knew. Women would continue running their households to keep moral on the homefront as high as possible while trying to keep their loved ones abroad in high spirits as well. Some would even take on positions in the workforce, albeit temporarily. African-American men, though struggling with the injustices of a legal racial divide still devoted themselves to the cause, with their wives and sisters standing behind them and the nation. The people of Scott County, and the men, women, and children of the United State of America banded together behind the cause for war regardless of race, religion, color or necessity because they were all Americans and thought it was morally what needed to be done. This unity is what helped the United States help win the First World War.