by Jacob Dalland

In a not-so-busy part of Savage, Minnesota, Eagle Creek widens out into an almost circular pool. A visitor’s first impression might be that it is a peaceful and quiet place, where Eagle Creek almost seems to rest before moving onward to its mouth on the Minnesota River. If by chance, however, a visitor comes at the right time or sticks around long enough, the water will ripple, gurgle, and even shoot upward a few feet. This is not a geyser, but a unique Maka Yusota, or otherwise known by English-speakers as Boiling Springs.

Maka Yusota is a Dakota phrase, coming from the word for “earth” (maka) and “to make muddy or roil up” (yusota). For centuries, the Dakota people have revered this as a sacred place, where the water spirit Unktehi resides. One oral tradition has it that Eagle Creek got its name from when an eagle flew out from the springs and turned into Buffalo Calf Woman, who guided the Dakota people also from the springs with the Sacred Pipe. The Dakota leader, Eagle Head had a village here for many years, and was formally vacated in 1853 as part of the 1851 treaty at Mendota. Apart from the exodus story in the Dakota oral traditions, Maka Yusota has also had sacred significance as a kind of oracle. One story tells of how in 1858 a warrior came to the springs and speared one of twelve lumps of earth pushed up to the water’s surface, which immediately seemed to bleed. This was interpreted to signify an imminent battle. The Battle of Shakopee, fought between the Dakotas and Ojibwes, occurred soon afterward.

By the time the Battle of Shakopee happened, the Dakota people no longer had the exclusive right to live on the land, and farmers were soon homesteading in the area. A French grape farmer briefly owned the land first in the early 1850s in what was then Glendale Township. In 1855, Gregor Hattenberger bought the farm and improved upon the grape vineyard. He also built and operated a grist mill and made wine from the grapes. A farmhouse was built only about 300 feet feet from the springs in the 1870s.

A close-up image of Boiling Springs in action, from a postcard in the 1910s. Scott County Historical Society.

The Hattenberger family, knowing that the Boiling Springs were not only sacred to the Dakotas but also unusual in their own right, soon opened up that part of their property to visitors of all backgrounds. By the turn of the century, Boiling Springs was essentially a privately owned park. Trees were cleared to make a trail and a picnic grounds, and visitors could watch the springs bubble from behind a fence. Back then, the springs bubbled constantly rather than sporadically. Before the fence was put up, an occasional cow or horse would die from sinking in the quicksand of the springs. The way the springs “boil” is thought to be from sand settling at the bottom, clogging the opening of the springs, and then erupting upward after the water pressure of the springs is great enough. Then the process would repeat.

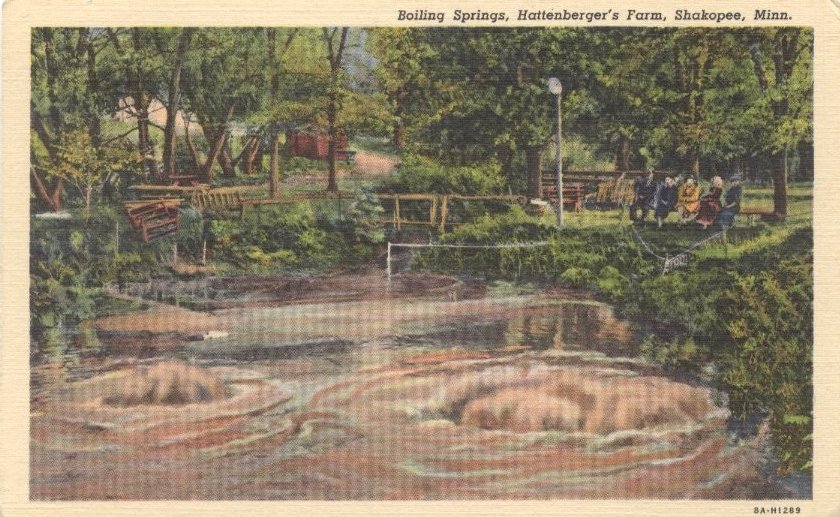

This color postcard shows how park-like Boiling Springs used to be. Despite being located in Glendale Township (now Savage), postcards often mislabeled the location as Shakopee. Scott County Historical Society.

The heyday of tourism at Boiling Springs seems to have been the first half of the 20th century. Photographic postcards of Boiling Springs were being made and sold in the 1910s especially. Every now and then, articles advertising Boiling Springs as a “natural wonder” would appear in local newspapers. Three generations of Hattenbergers hosted visitors to the site: Gregor, Alexander, and Alois. The Hattenbergers offered homemade wine, replaced by ice cream and candy in the ‘20s through ‘40s.

After Alois Hattenberger died in 1953, his cousin Herb Hirscher ran the farm and continued to provide hospitality to visitors. During the Hirscher years, the springs started to quiet down, possibly due to a lower water table. Therefore, the springs started to lose attention, though people could picnic there as late as 1959. Dakota pilgrims never ceased to visit during the Hirscher years, either. That being said, tourism was definitely on the decline at Boiling Springs from the ‘60s through ‘80s. The Hirschers commented in 1985 that Boilling Springs “was lovely in its day.” Herb died in 1986, leaving his wife to run the farm for a time. The Hirschers hoped that after they were gone, Boiling Springs would be preserved by the Minnesota Historical Society or some other public entity.

The Hirschers’ and more importantly the Dakota people’s hopes of conserving Boiling Springs were put to the test in 1994. That year, Lucille Hirscher sold her farm to Klaas van Zee, a developer for the City of Savage. Almost immediately, a struggle ensued between members of the Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community and environmental advocates on one side and real estate developers on the other. There was a very real threat that the construction of a new suburban neighborhood on the site would not only ruin Boiling Springs and the Dakota burial sites around it, but also threaten the habitat of brown trout (whose Eagle Creek habitat was one of the last in the Twin Cities) and many other animals. After a year of petitions and debates, the two sides essentially compromised. The City of Savage was allowed to build a suburban neighborhood on some of the former Hirscher farm, but the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources bought all the land within 200 feet of Eagle Creek to preserve as an Aquatic Management Area. The old farmhouse was unfortunately outside of this zone, and was subjected to a deliberate burn to test new firefighting equipment in 1997. Boiling Springs, on the other hand, continues to be conserved in its natural state by the DNR and has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places since 2003.

Today, Boiling Springs lies within a grove of trees, almost concealed from the view of the houses nearby. Apart from minor trails made by the tread of occasional visitors’ feet, nobody would ever know the springs were widely visited in the past. Maka Yusota, Boiling Springs, is nonetheless one of the most significant places in all of Scott County.

References

Bloomberg, Britta. “Recent Additions to the National Register of Historic Places”. Minnesota Preservation Planner 14, no. 2 (Spring 2003): 2.

“Boiling Springs” (postcard).

“Boiling Springs, Hattenberger’s Farm, Shakopee, Minn.” (postcard).

“Boiling Springs Natural Wonder”. Shakopee Tribune, November 5, 1925, 3.

“Boiling Springs, Natural Wonder of Area, Reopened for Picnickers”. Shakopee Valley News, June 18, 1959, p. 1.

“Boiling Springs Near Shakopee Termed Unusual Phenomenon”. New Prague Times, November 25, 1925, p. 1.

Brewer, Joseph W., to Heald, John. “Comment Statement: Alternative Urban Areawide Review for Savage Fen, Eagle Creek, and Boiling Springs Development”. November 7, 1994.

Durand, Paul. Where the Waters Gather and the Rivers Meet: An Atlas of the Eastern Sioux. Faribault: Paul Durand, 1994, 44.

“Hattenberger Rites Monday”. Shakopee Argus Tribune, September 10, 1953, p. 1.

“Herbert A. Hirscher”. Shakopee Valley News, July 2, 1986, p. 6.

Hirscher, Herb and Lucille. “Boiling Springs”. In As I Remember Scott County, 1980.

Kaszuba, Mike. “Old Farmhouse in Savage Runs out of Time – and Luck”. Star Tribune, November 30, 1997, p. B1.

“Remember When...” Savage Pacer, February 19, 2005, p. 5.

Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community. “MA-KA YU-SO-TA (Boiling Springs)”. September 2000.

Simonson, Beverly. “Savage Woods Once Echoed with Sounds of Legendary Springs”. Prior Lake American, October 19, 1977, p. 3.