Spring is beginning to peek in from between the piles of snow, and Minnesotans from around the state are turning their attention towards their lawns and gardens.

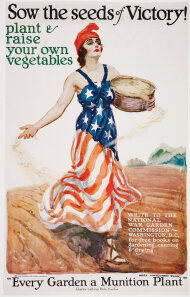

A hundred years ago, that attention was cast as patriotic as well as recreational. As the United States entered World War I, food production was in the forefront of war preparation efforts.

Between the Civil war and World War I, cooking and kitchens were transformed in America. Iceboxes were being slowly replaced by refrigerators, invented in 1913. Farming changed too as gas powered tractors were becoming a commonplace sight in Minnesota’s fields. Crop, husbandry and soil research from large land-grant universities was making a difference in the daily lives of farmers. As A. D. Wilson, the director of the University of Minnesota said at the time “The changed conditions are placing more and more bright progressive men and women on our farms who are not ashamed to study their profession and put their best efforts into it. As a consequence, we are developing a true science of agriculture. We no longer depend on ‘chance’ or ‘good luck’ for results in farming but know the conditions necessary for good luck”. Scott County got into the game too. Entire pages of the Scott County Argus were devoted to the latest Agricultural research, with rousing headlines such as “Sugar Beets and Mangels Tend to Increase Milk When Fed to Dairy Cows but Corn Silage is Far More Economical” and “Prevention of Corn Smut Through Formaldehyde Use”, both appearing on March 16, 1917.

Less than two weeks after war was declared, President Hoover issued the proclamation “We must supply abundant food for ourselves and our armies… and for a large part the nations with whom we have now made common cause… without abundant food the great enterprise which we have embarked upon will break down and fail”. In 1917, approximately half of Minnesotans lived on farms, and many of them began to view their efforts as essential to US victory.

An editorial published in the March 9th 1917 issue of the Scott County Argus declared:

“With conditions like these everyone who has a piece of ground should plant some food products. Most all of the large cities in the country are entering the worldwide movement of greater food production. If Shakopee does not do her part in this great movement it will not be the fault of her public school teachers, for all boys and girls are being encouraged to take up some form of the work and more encouragement from the homes of our young people is needed…Education should help us live better NOW as well as later in life, and NOW is the time for the young folks to get into the game.”

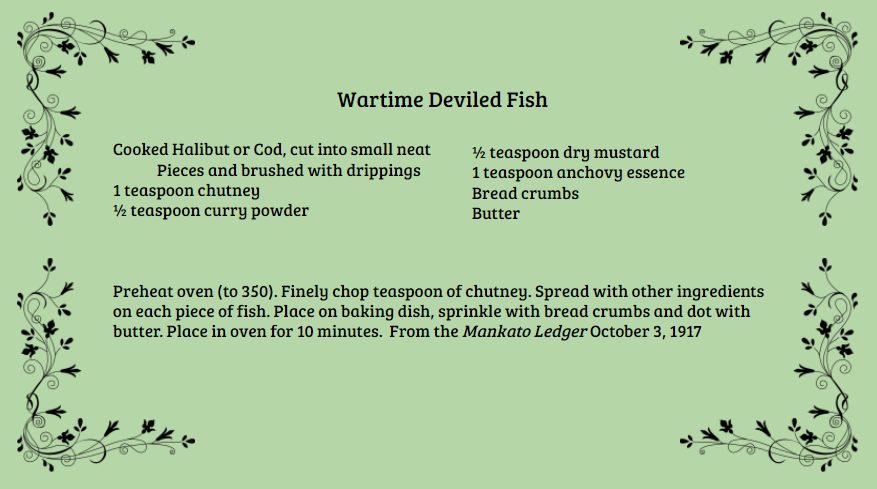

A much shorter letter to the Argus published on May 18th 1917 advocated “Minnesota can aid materially in averting a food shortage during the war and save millions of dollars annually on food in times of peace if we will take steps to utilize the millions of fish that inhabit the lakes”

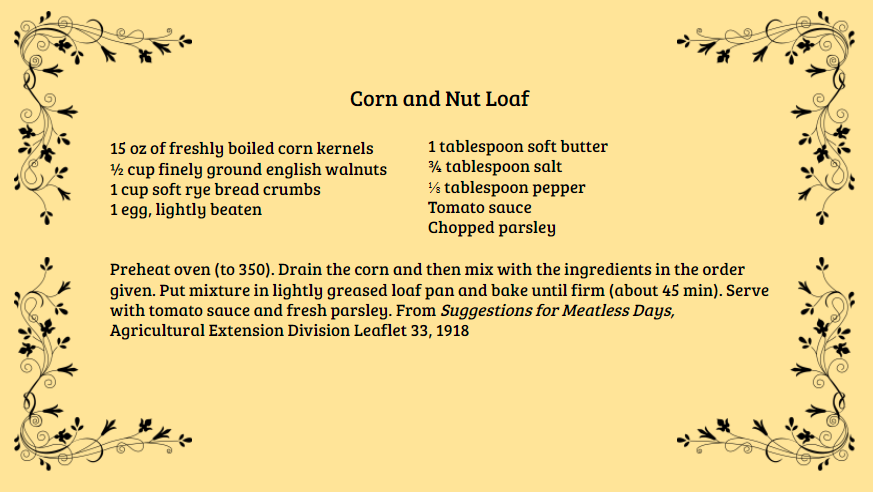

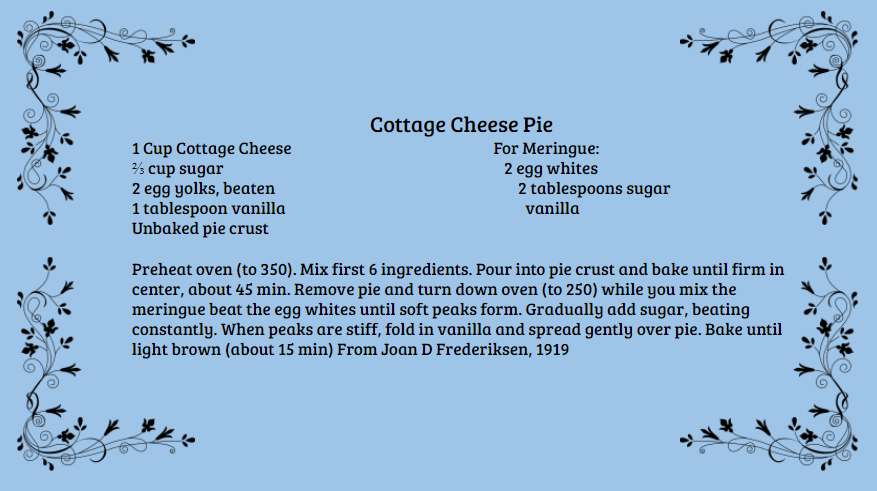

During the war, meat and sugar were deemed important for the creation of foods which could provide compact calories for shipment abroad to feed soldiers and allied nations that were directly impacted by the fighting. Americans were also encouraged to conserve wheat so that bread could be distributed to hungry troops. In exchange, Americans were asked to use more milk, fish, and grains such as oats and corn

Throughout these efforts a lot of emphasis was put on the role of women. While most men and women still operated in distinct spheres during this time, the war provided the need and opportunity for female leadership, particularly in the role of food conservation.

The Minnesota Commission on Public Safety was organized in the spring of 1917 and a women’s auxiliary was created simultaneously. The sentiment of this organization was summed up thus in the May 1917 issue of Farmers Wife Magazine: “With the farm women lies the sacred charge of serving this nation in its hour of peril… on farmers’ wives and daughters, in large measure, rests the fate of the war and the fate of the nations”. The April 20th 1917 issue of the Scott County Argus described the creation of a statewide committee on food preservation and conservation by the governor. The article lists as one of their primary duties “… to encourage home economics and the organization of groups of town women to assist farm women in harvest and other periods of labor stress”.

The Woman’s Committee booth at the 1917 Minnesota State Fair

The efforts were not without humor. A poem in the January 2018 issue Northfield Norwegian American described rationing with these words:

“Oh gone now are the good old days of hot cakes thickly spread

And meatless, wheatless, sweetless days are reigning in their stead

And gone are the days of fat rib roasts and two inch t-bone steaks

And doughnuts plump and golden brown, the kind that mother makes

And when it comes to pies and cake, just learn to cut it out”

Mr. Hoover’s goin’ to get you if you don’t watch out”

In terms of sheer volume, these efforts were largely successful. In first year of war the US shipped 9 million more tons of food overseas than before the war, approximately a 250% increase. Listed below are a selection of recipes shared in Minnesota newspapers to help their readers practice conservation of sugar, wheat and meat in the kitchen. For more recipes and local war stories, visit the “The Great War” exhibit currently on display at the Scott County Historical Society. Let us know your results if you try any of these recipes!

Written by Rose James, SCHS Program Manager