This story is written by guest blogger Charles Pederson. To write for our blog, email us at info@scottcountyhistory.org

Part 1 described the roots of the county seat controversy and the first two attempts to move the seat to Jordan. In Part 2, learn about Jordan’s continuing efforts to bring the county seat to that fair village. And prepare for a surprise plot twist.

Third Attempt to Move the County Seat: 1876

Jordan had already made two previous failed attempts to move the county seat from Shakopee to Jordan. Ever optimistic, though, Jordanites began agitating again for the county seat to move. The scheming began in early 1874, not long after the previous attempt. Jordanites wrote to John Macdonald, Minnesota senator from Shakopee. Their letter’s sentiments fit right into today’s political climate: “We deem any opposition to the passage of the bill [to move the county seat] a sure manifestation of an unwillingness to submit to the voice of the people . . . [and] a desire and intent to defraud them of their rights. . . . Should you refuse us in this request, we shall hereafter consider you unfit to hold any office of public trust.”

In 1876, a bill passed the house but not the senate. The Jordanites again had to accept defeat and gather strength for their next attempt.

Fourth Attempt: 1878

Despite their numerous unsuccessful attempts, Jordanites helped introduce another legislative bill in March 1878 to move the county seat. The motion was defeated—and the residents of Shakopee held a huge reception and party for their senate representative, who had helped defeat it. However, a measure was passed allowing both Jordan and Shakopee to issue bonds to buy land and build or improve county buildings on it. Jordanites doubtless hoped this was their chance to get the county buildings themselves. But the measure was not acted on.

Fifth Attempt: 1889

Like a cicada, the controversy lay dormant for the next eleven years before surfacing again. Shakopee’s place as the county seat seemed to have become fixed and permanent. In 1889, however, as required by Minnesota statutes, a legally recognized petition was presented to the county commissioners. Alas for Jordan, most of the members voted to disregard it, apparently ignoring their duty.

Whence the residents of Jordan got the energy to continue the fight is speculation. In 1890, though, Jordanites convinced a judge to order that the board must consider the petition, as it was legally bound to do. At a February hearing before a Minnesota Eighth Circuit Court judge, the petition was again denied. Julius Coller, a staunch Shakopee cheerleader, wrote with ill-concealed elation that this “dashed the hopes of the would-be Court House removers.”

Sixth Attempt: 1927–1929

Three decades—and a new century—later, the county needed a new courthouse. One cost estimate for a new courthouse was $160,000 (approximately $2.5 million in 2021 dollars). Commercial interests in Shakopee logically imagined that this could lead to another fight over the county seat. To head off that possibility, a private group retained an architect to look at the building. He reported that a new courthouse was not necessary, that simply updating and remodeling the existing structure would be enough. Still, his repair and remodeling estimate was $65,000—more than $1 million today. Though a hefty amount, it was far less expensive than constructing an entirely new building elsewhere (in, say, Jordan). The board accepted that estimate, but Shakopee’s dreams of peace were dashed when the town was forced anyway to defend its status as the county seat.

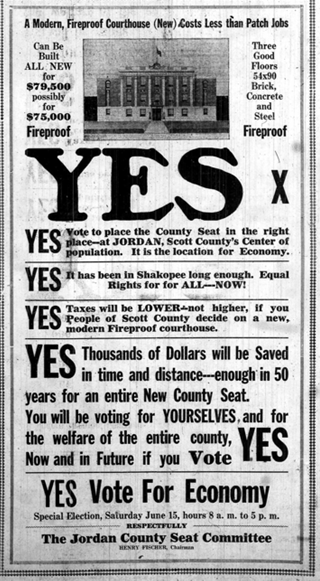

Each side in the controversy placed ads in local newspapers to convince voters of the righteousness of their cause. This pro-Jordan ad appeared in the Jordan Independent of June 13, 1929. Scott County Historical Society Collection.

Just as the momentum for a fight between Jordan and Shakopee—those two old contestants—was building, the rivals must have blinked in shock when a surprise contender entered the fray. A group of residents in Lydia (population 60), seven miles east of Jordan, gave notice of intention to circulate a petition to bring the new courthouse to their town, thus winning the county seat. On November 4, 1927, Lydia residents leading the charge circulated a petition to that effect. Jordan, no doubt kicking itself for being late to the show, circulated a similar petition a week later. By mid-November 1927, canvassers of both towns were busy throughout the county, asking voters to sign their petitions.

What followed was a welter of confusion and rancor. Both Lydia and Jordan met the minimum legal number of signatures for their petitions. Lydia’s eight-day head start should have guaranteed that it be considered first for the county seat move, and indeed, the state Minnesota Supreme Court upheld that view. Both sides were anxious because Minnesota law stated that an election on the question could occur only every five years. Both wanted to strike while the iron was hot. Who knew what political conditions would be like in five years?

Lydia sued to halt Jordan’s petition “on the grounds,” said Lydia banker Martin Imm, “that Lydia announced its intention of obtaining the courthouse before Jordan did and therefore is entitled to file its petition first.” The suit was denied. Lydia then filed notice of appeal all the way to the Minnesota Supreme Court. In response, a Jordan backer obtained a restraining order to halt consideration of Lydia’s petition. Ultimately, the Supreme Court decided that Lydia’s petition had precedence over Jordan’s and could be considered after all.

After all that, the state attorney general ruled that signatures in the Lydia petition were invalid. As found in the 1905 Minnesota statutes, the petition had been filed, and the county board met to decide which, if any, of the signatures to said petition [were] not genuine; and which, if any, of the signers thereof were not, at the time of signing the same, legal voters of said county; and which, if any, of the signatures thereto were not attached within sixty days preceding the filing thereof; and which, if any, of such signatures have been withdrawn.

In other words, the board decided which names on the petition were invalid. More than 700 names were withdrawn from Lydia’s petition. Coller happily reported, “The petition was subsequently rejected.” Undoubtedly with much weeping and gnashing of teeth, Lydia was knocked out of the running.

Lydia’s exit from the race left only Shakopee and Jordan. There were charges of malfeasance, dire warnings of higher taxes, and claims of prejudice against one town or the other. Jordanites claimed Shakopee was avoiding paying taxes. Shakopee replied with outraged explanations why that was untrue.

Each side sent out representatives to speak with voters, and numerous articles appeared in local newspapers, trumpeting why each town was superior to its rival.

Attempting to rouse their supporters, Jordan and Shakopee took their show on the road throughout the county, attempting to rally their supporters in towns and townships during the week leading up to the election. A feature of at least one rally “was the large number of ladies present,” as reported in the Jordan Independent. This might not seem so remarkable until one remembers that women had gained the national right to vote less than ten years previously.

The Shakopee–Jordan county seat battle culminated in a special election in June 1929. This sample ballot instructs voters how to place an X to indicate their choice. Scott County Historical Society Collection.

Finally, election day, June 15, 1929. A majority of county voters decreed that Shakopee retain the county seat: 4,428 voted to keep the county seat in Shakopee, and 2,533 to move it to Jordan. The vote included “approval of the Shakopee proposal to remodel the old courthouse instead of building new,” according to the Jordan Independent. The newspaper continued, “Shakopee was jubilant over its big victory and celebrated in happy abandon Saturday night, Sunday and on.” Church bells, car horns, fire sirens, and huge crowds distinguished the celebration.

They All Lived Happily Ever After?

This 1929 push marked the end of efforts to move the county seat from where it had been for seventy years and has remained for ninety more. Perhaps, however, Shakopee shouldn’t feel too smugly complacent. The law on changing county seats remains in the 2020 Minnesota statutes. You never knowwhen the fight may kick up again!

Further Reading

2020 Minnesota Statutes. (2020). Chapter 372. Changing county seats.

Coller, Julius. (1976). The Shakopee story. North Star Pictures.

County News: County Seat Rallies. (1929, June 13). Jordan Independent [newspaper], p. 8.

County Seat Contest: Its Lessons. (1872, November 9). Scott County Mirror [newspaper], p. 1.

County Seat to Remain in Shakopee, Say Voters. (1929, June 20). Jordan Independent [newspaper], p. 1.

Court Fight Planned By Lydia, Imm Says. (1927, November 17). Jordan Independent [newspaper], p. 1.

Dunnell, Mark B. (Ed.). (1905). Revised Laws Minnesota. Sec. 396ff. State of Minnesota.

High Court Gives Lydia Priority. (1928, May 17). The Peoples Weekly [newspaper], p. 1.

Minnesota Digital Library. (n.d.). Men at Scott County Courthouse, Shakopee [Photograph ca. 1895].

Remodeled Courthouse Will Meet Scott County’s Needs. (1929, June 13). Jordan Independent [newspaper], p. 2.